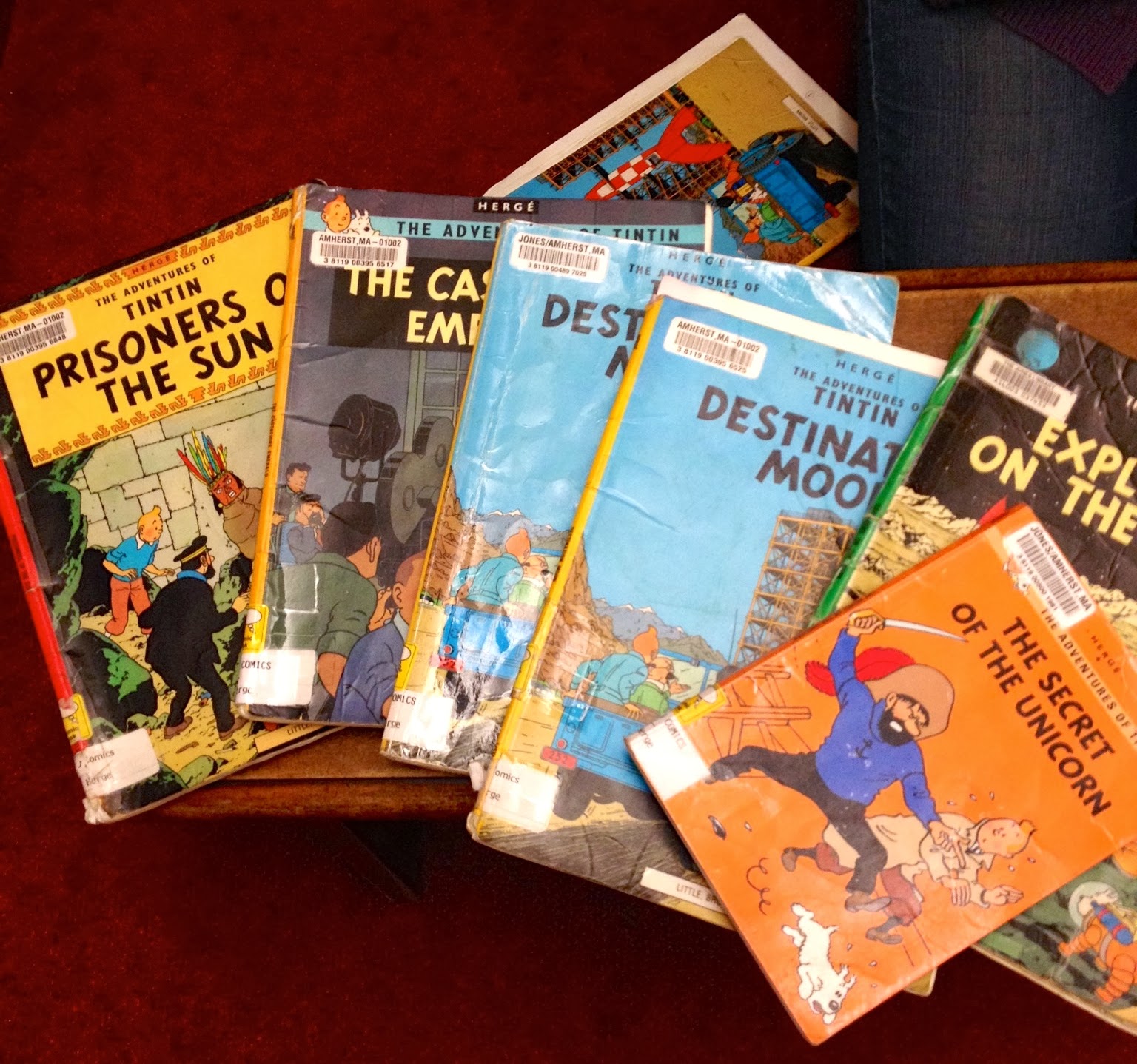

Well worn copies of Tintin at the Jones Library

So it turns out the only Jones Library copy of the most offensive entry in the "Tintin" series -- "Tintin In The Congo" -- is in french, so it is located in the foreign language section, and not with the other ones (pictured above) at the higher profile entryway to the Children's Room.

Of course when I asked to peruse "Tintin in the Congo, " err, I mean "Tintin au Congo" it was, naturally, already taken out. Not that I parle francais.

A really long-time Jones Library employee confirms the Tintin series has been available since she first arrived at the Jones back in 1972, and replacement copies have been ordered over the years (English versions of course) because they have worn out from avid readership.

Library Director Sharon Sharry also confirmed that the most recent written “request for reconsideration of library materials” filed by the concerned parents over Tintin was the first such formal request she has had in her 17-month tenure thus far at the Jones.

Back in 1996 a traveling photo exhibit "Love Makes A Family: Living in Lesbian and Gay Families" sparked controversy in Amherst because some parents did not want their elementary school aged children exposed to it.

Although they were a tad vague as to what "it" was that children needed to be protected from.

The schools stood firm, the photo exhibit went on (probably to a much wider audience because of all the controversy) and our local civilization did not fall.

Censorship is censorship. A doomsday device -- no matter which political persuasion employs it.

22 comments:

Asking for a material to be relocated is different from working to entirely disallow it. And comparing a photo exhibit whose entire purpose was to challenge stereotypes with a book series that clearly functions to reinforce many of those same stereotypes, makes absolutely no sense. I get where you're trying to come from here, Larry, but your argument doesn't hold water.

As Director Sherry stated (according to your post): the most recent written request for reconsideration of library materials filed by the concerned parents over Tintin was the first such formal request she has had in her 17-month tenure thus far at the Jones. This isn't an instance of library staff and trustees needing to hold off a flood water of controversy and unrest about the appropriateness of library materials in general. It is an example of a single thoughtful query about where a particular (currently child accessible) material of a clearly outdated and inflammatory nature might best be housed.

Anonymous 6:16, many people in these parts find literature that functions to reinforce gay normalcy as offensive as any adventure of Tin Tin. This is why you can't censor any of it. Everyone has an opinion. Viewpoints have no right or wrong. It's a libraries job to be an informational source, not a judge of history through oppression and censorship. A path of education and awareness helps alleviate stereotypes, not censorship. Censorship only divides and feeds ignorance.

(I'm continuing a thread here that began on Larry's first post on the topic...)

Christopher, was the library's decision to continue to keep the book at it's current location in the building based at all in a belief that to move the book to another location within the library would amount to censorship, or a "banning" of the material, or in a belief that the book would become less accessible?

People should really read TIn Tin in the Congo before they take a position on it. It is very offensive, way over the top. I doubt you could find an English language version sold in the United States since we are way ahead of Europeans on the race issue, as they sturggle with the consequences of colonialism on their own lands, finally. Give Congo the boot and keep the rest.

Has the Library ever recategorized or otherwise changed the location of a particular book within the library?

In articles from across the country, the library director is quoted as saying that: "'relocating the books would amount to censoring them', citing the American Library Association’s definition of censorship as a “change in the access status of material, based on the content of the work and made by a governing authority or its representatives.” This can include changing the age or grade levels that have access to the material." and “If the Jones Library does nothing else, we protect everyone’s constitutional right to read anything he or she wants,” Sharry said.

Again...a change in category does NOT change "the age or grade level that access to the material"--any kid of any age or grade level can access any part of the library and it's collection--nor would it affect anyone's "constitutional right to read anything he or she wants".

I believe that according to the ALA's website definitions on their "Intellectual Freedom and Censorship Q&A's" page that the request does not meet the definition of censorship. The word "censorship" has been bandied about way too much, I think applied incorrectly.

It's not like every piece of material has to be right in your face or otherwise it's not accessible...a book high on a shelf deep down in the stacks is not less accessible to me than a book that the library staff choose's to make a display out of as I enter the library. It may be more conveniently located, but NOT less "accessible".

What criteria does the library staff use when "weeding" the library's collection?

What is the difference between restricting people's access to be a book by "weeding" it out of the collection (with no public input I assume?) versus moving it's location within the library?

I doubt you could find an English language version sold in the United States

REALLY????

I found it the first place that I looked (Amazon) and the most difficult thing was realizing it was "Tin Tin" and not "Rin Tin Tin."

People should really read TIn Tin in the Congo before they take a position on it.

It was actually part of the eulogy at his funeral -- Voltaire never actually said it, although the classic "Voltaire" quotation is:

"While I disagree with everything you have to say, I will defend to the death your right to say it."

I have no intention to waste my time reading it, but that doesn't mean that I won't defend the book -- and there is a distinction there

By the same token, and with the exception of when they advocate violence, I'll defend the right of the Critical Race Theorists to promulgate their drivel. All I ask is the opportunity to (1) point out that no court, anywhere, ever, has agreed with them, (2) thus this is not what the law actually is, and (3) they are some of the most racist and prejudiced bigots you will find anywhere.

Milton put it best, saying something to the effect of truth, being stronger than falsehood, will inevitably prevail in a fair fight.

If your children don't already understand the concept that racism is bad, that's your fault -- your failing as parents. If your children are so devoid of moral character that mere exposure to one rather sophomoric book will erase every moral value you ever taught them -- again, that's your failing as parents.

It's not the book.

Books aren't inherently dangerous the way firearms, automobiles and chain saws are -- you'd have a valid point if the library was handing out running chain saws to 10-year-olds. There are real issues with secret curriculum (e.g. Common Core and when critical inquiry becomes replaced by indoctrination (e.g. Common Core, not to mention presenting adult topics such as sexuality to children who are neither physically nor psychologically mature enough to understand them.

Outside of those shoal waters, one can safely say that no book will ever hurt a child. In fact, not having books does -- and that is how we wind up with more young Black men in prison than college, but I digress.

It is very offensive, way over the top.

As opposed to, say, the literature of the "sodomites"? And yes, there are people (a significant majority of the country) who believe Leviticus 18:22 to be a mandate from God, that "[t]hou shalt not lie with mankind, as with womankind: it is abomination" means exactly what it says.

It's a very slippery slope you go down when you start talking abut banning books out of fear that children will become corrupted by the ideas contained within them.

If your children are that vulnerable, you've got a lot bigger problem, and there are a lot more temptations than a dusty book in the library.

"...comparing a photo exhibit whose entire purpose was to challenge stereotypes with a book series that clearly functions to reinforce many of those same stereotypes, makes absolutely no sense."

In other words: Views I agree with, good; views I disagree with, bad.

This is the mistake the left has made -- instead of defending its values on their merits, the Left has spent the past 30-49 years simply silencing all other viewpoints -- which is all fine & good as long as you have a perpetual hold on power. But no one ever holds onto power in perpetuity and the era of the left is waning.

What the left will discover, to its chagrin, is that the concepts of free speech which it destroyed won't be there for it when the right assumes power.

Understand, boys 'n' girls, that whatever precedent that is established with TinTin in the Congo will almost inevitably be eventually applied to Heather has two mommies.

Another quick reply while I have a second.

Kurt: moving the book to a different section is censorship, in the sense that the only point for doing that was to restrict access for a certain class of people, who are in fact the audience for the material. It's not enough to say that those who already know about Tintin can ask the librarian how to find it. It is a series written for young children, mostly read by young children, therefore putting it any place other than where young children can easily come across it is a restriction on their rights as library users.

As one ALA interpretation I read put it: every library user, including minors, must be considered to have First Amendment rights. A bit later it also makes clear that the choice of what material is appropriate for any child can only be made by the parent of that child and not by any other child's parent. Nor, by extension, is it the library's job to act as a parent and do anything that is intended to restrict access to material by the part of the public that has an interest in that material.

And, yes, that includes "Tinin in the Congo". If there genuinely was public demand to put an English language copy in the Children's Room, not doing that because we, or some other members of the public, find it offensive, is wrong. Looked at another way -- if there were such demand, the problem (for those of us who feel that it likely was a sign of a problem) lies in the community. Proper ways for a public library to address such problems is to provide more information, education, materials, etc to the community. But, as I understand the issue, as soon as a public library's answer to a problem involves the word "restrict", you know are doing something wrong.

Ed said: It's a very slippery slope you go down when you start talking abut banning books out of fear that children will become corrupted by the ideas contained within them.

and when someone in Amherst starts "talking about banning books" we should seriously address that issue. But no one has suggested that. It's a "slippery slope we go down" when we start accusing individuals who went through appropriate protocol to have a concern addressed, of ideological beliefs they don't seem to possess.

We can't seem to come to an agreement on what was or was not requested. The library Director has said that re-categorizing a book, or moving a book to another location in the library, would be censorship of that material, but that does not agree with any definitions of censorship I can find anywhere.

I wish we could get some clarification on that detail, specifically, what source did she refer to that includes the definition of "censorship" that she based her decision on.

This post makes me want to read Tin Tin in the Congo

I think that the word "censorship" may be confusing things.

The question is: what does the reasonable, prudent, principled library do?

The Director looked to ALA standards for that.

Re: anonymous 12:00

Dictionary.com defines "censor" as "any person who supervises the manners or morality of others".

The ALA defines "censorship" as "the suppression of ideas and information".

Whether you consider moving books to be literal censorship may depend on whether you think "suppression" can only mean an outright ban, or if it includes deliberately making it hard for the intended audience to be exposed to the material.

But regardless of the term used, the concept of cataloging materials based on who finds them offensive rather than who wants to read them is clearly not sanctioned by the ALA.

All the Tin Tin books on Amazon have 4 plus stars in terms of reviews and if you scan though the reviews many say they aren't as racist as they thought.

Censorship never did anything but make things worse. If you don't want your kid to read it, then don't let him/her. Many of us do and we would like our right to be able to do that upheld.

I think I've addressed Kurt's questions on the other thread, except for "Does the library EVER re-categorize a book? For what reasons? Does moving a book's location each time mean they are making it less accessible? What about when books are de-accessioned or discarded? Does the library's decision to discard a book mean they don't want to make it accessible, i.e,. "censorship"? What criteria does the library use to decide whether or not a book gets discarded? And who makes that final decision? Why would/should the decision be left solely up to one or two librarians and not the people who support the library with their tax dollars?"

I'm a trustee, not a professional librarian, so I can't tell you the details of categorization and weeding. But I can say that as I understand it, it is almost entirely about public demand vs our budget.

Books are weeded because they are physically falling apart, or no one seems to have read them in ages, or they are so old they are "unreliable informational resources" (which is not the same as "contain outdated racial attitudes"!). If they are not replaced with new copies, the library then as space for books with more recent information, or about topics that our current patrons are more likely to want to read.

Ditto for categorization. Mostly this is based on who's checking out the material, or who the publisher/author expects to want the material if it's something new. Sometimes local librarians adjust this -- I think the Director's example was a young adult biography of an athlete might get put under either the sport or general biography -- but that's done to make the material easier to find for the intended audience, not as a value judgement about who isn't ready to read it!

So in essence, yes it is indeed the taxpayers who who decide what's in the library collection, both by indicating the books you want to read and backing that up via checking them out, and by showing your approval of the job we're doing via ensuring our town funding and contributing to our various fund drives (thanks to all who have done that this year! Have you heard about the Sammy awards yet???)

I'd also like to put in a good word for the parents. They handled this exactly right. They made sensitive, well-researched, thought-provoking and intelligent arguments.

They weren't trying to ban a book series, they wanted it re-categorized. They weren't hippy liberals being politically correct, they were same-sex couples, people of color, etc, most of whom had experienced alienation as children and now wanted to protect their own kids from that. They weren't asking the library to do their job in pre-reading the books. They already were checking on what their kids wanted to read so they'd know if there were concerns. When found saw something, they went through exactly the right process to express concern.

What they were worried about wasn't their children's exposure to Tintin, but what happens if their children have to deal with other children who treat them differently due to what they've learned from Tintin.

It's not a bad thing to want to protect your kids or to prevent racism. But as I see it, a public library can't help them in that by in any way discouraging those other kids from reading Tintin, or any other problematic book, nor by trying to be "better" parents for those other kids. It can, and I guess already are starting to, take part in a discussion about what what's in the books our kids are reading and how they can be made into positive lessons.

Thanks for taking the time Chris, you've really clarified the decisions and the processes everyone went through. Also I think you've countered well many of the reactionary anonymous comments on here and on previous posts that were clearly intended to demonize the parents who made the request.

That last comment was mine. Kurt Geryk

Chris, thanks for all your comments!

Chris Hoffman: thank you for your comments on this blog post. They are very helpful.

The intended readership for the Tintin books as described on various bookseller web sites is children ages 8 and over, in other words, grade 3+. My children first found the Tintin books when they are 4 or 5 years old because the books are located in such a high profile spot, at the entrance to the children's room and at floor level, and I thought the content wasn't appropriate for them at that age. Would it be considered restricting access to the Tintin books for them to be moved to the main grade 3-5 section?

An aside comment/question: Does having the children's biographies located upstairs seem like it might affect their use and circulation? I personally wish they were located closer to the rest of the children's section. I am sure that the layout of the children't section was planned out with considerable effort and time, but would it make sense to ever revisit which books and other materials are located where?

Not all non-fiction books, by any means, that are "old" are "unreliable sources of information", I don't think I need to cite examples as there are literally thousands and thousands. And fiction books are regularly weeded and they are not "sources of information" but sources of entertainment.

Who makes the subjective decision to eliminate a book from the library's collection based on that principle, that they are "unreliable sources of information". I don't imagine that popularity and records of how often a book has been borrowed is the only criteria someone (and who actually does the "weeding"?) as some classic works that belong in any collection might sit collecting dust for many years.

(And of course I'm not talking about things like really old biology or computer science text books, even though they are sources and examples of past educational material that people do research on.)

anonymous 11:58 & 5:14

I'm not a librarian, so I can't answer your questions for certain.

Regarding the layout of the children's room. Actually, the current layout is showing its age and the fact that the biography section is harder to get to is one example! Revisiting the layout is quite appropriate. But the key thing is that changes will be made to improve access to the collection, not apply value judgements.

My youngest kid is 18, so I no longer have a detailed knowledge of all the sections that are there. It might be there is a better location for it. But the definition of "better" has to be that it improves access for those who might be interested in the book, and maybe that would be where the grade 3-5 people look rather than preschoolers.

Regarding weeding "old" things. I actually copied that from a previous poster, who may have gotten it from the humorous website awfullibrarybooks.com. If you read that site you'll know the outdated information they're talking about tends toward 1970's books about computers or the people of country X, where X doesn't even exist anymore. And they always point out even these books might be appropriate to keep for their insights into their eras. But not as active reference books. For fiction I think it mostly comes down to whether people are still checking it. Of course, this isn't an entirely mechanical, objective, criteria. But the objective is to keep books that people want to read, not what the librarian thinks they should read.

Post a Comment